Where Can I Buy Sinclair Paint

Where is the world's about expensive painting?

(Epitome credit:

Corbis/Getty Images

)

Ii new documentaries delve into the ongoing saga of Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi in a moment when true fine art crime stories are at their meridian, writes Caryn James.

Due south

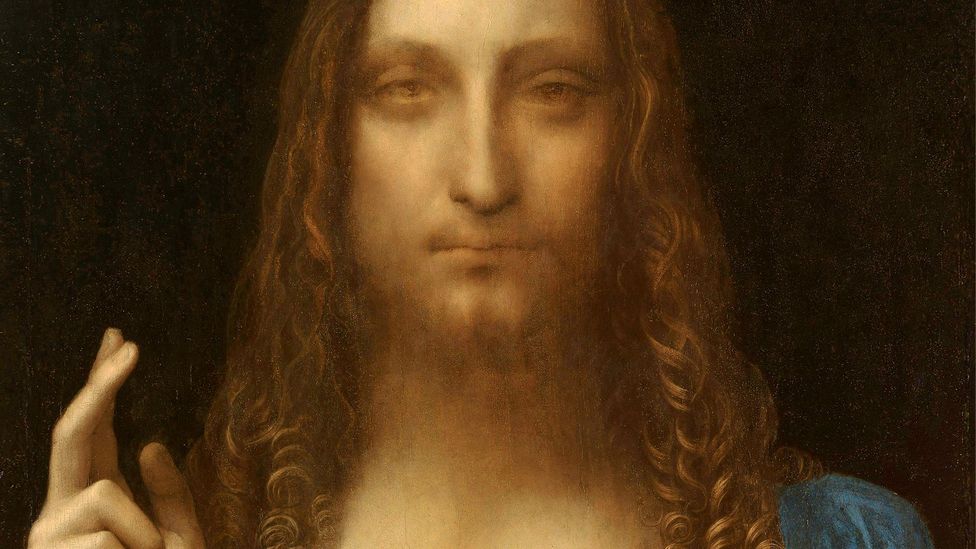

Somewhere in Kingdom of saudi arabia, subconscious away by order of Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, is the world'due south nearly expensive painting, Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi. Or is it? No i in the art world knows for sure where the painting is. Most observers agree that it is likely stashed in the Heart East, merely some have speculated that it is stored in a tax-costless zone in Geneva or fifty-fifty on the Prince'south half-a-billion-dollar yacht. Is information technology fifty-fifty a Leonardo at all? The image of Christ as The Saviour of the World was billed equally The Last da Vinci at Christie's 2017 auction, where it sold for a record $450 one thousand thousand (£342 million) to a proxy for bin Salman (yes, that bin Salman, whom the CIA found responsible for ordering the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi). But fifty-fifty then, many Leonardo experts were dubious that the painting had more than a few castor strokes by him, and those doubts have ramped upwardly ever since.

More like this:

- The world's greatest art detective

- The men who Leonardo da Vinci loved

- The item that unlocks the Mona Lisa

Veiled in layers of mystery and international intrigue, the story of the Salvator Mundi is an ongoing, incessantly fascinating saga, told in two new documentaries, The Lost Leonardo and Saviour for Sale: Da Vinci'south Lost Masterpiece?, which play out with all the drama and suspense of a detective story. They arrive in the wake of Ben Lewis's high-profile 2019 book, The Terminal Leonardo, and dozens of manufactures. The painting, which dates to around 1500, was lost to history for more than 200 years, was damaged and desperately restored, and was sold and resold as a minor piece of work, probably by a Leonardo acolyte. Simply now the Salvator Mundi has become the poster male child for the volatile mix of money, power and geopolitics that defines the fine art earth today.

"When nosotros chose the title," Andreas Dalsgaard, a producer and a author of The Lost Leonardo, tells BBC Culture, "the inspiration was partly that the painting is lost right now and the truth is lost, but information technology was also inspired past movies similar the Indiana Jones movies that are full of treasures and treasure hunts."

This possibly-Leonardo treasure's road to fame began when it surfaced at an obscure New Orleans auction house in 2005 and was bought past 2 New York dealers for a measly $one,175. They brought it to Dianne Modestini, a highly respected restorer, who removed decades of grime and overpainting, and was the first to suspect information technology might exist a truthful Leonardo.

Art restorer Dianne Modestini in a scene from The Lost Leonardo, one of two new documentaries about the Salvator Mundi (Credit: Sony Pictures Classics/Amusement Pictures)

With its sleek narrative and a wide range of voices from dealers to art historians to investigative journalists, The Lost Leonardo is the ameliorate of the two films, and benefits greatly from using Modestini as its master graphic symbol. She is a captivating, elegant presence on screen, with a whispery voice and wide eyes behind signature black or red-framed spectacles. She spent years restoring the painting, and passionately defends its authenticity in precise particular, pointing out the pentimento nether Christ's thumb or a curve of his mouth that could but be Leonardo'due south. Only many experts think she did a drastic over-restoration. In the film, the art historian Frank Zöllner, who has compiled a catalogue raisonné of Leonardo's paintings, wryly calls the Salvator Mundi "a masterpiece past Dianne Modestini," who made it "more Leonardesque than Leonardo had done." For her function, Modestini has documented her work and the scientific studies of the painting, and published them online.

Most experts today agree the painting was probably produced past administration in Leonardo's workshop, where he added some finishing touches – a common practice. But uncertainty is key to the appeal of every version of the story, equally Lewis tells BBC Culture: "Nobody knows if information technology is a Leonardo, and then you too tin can play the game, y'all can do your own Da Vinci Code on the Salvator Mundi."

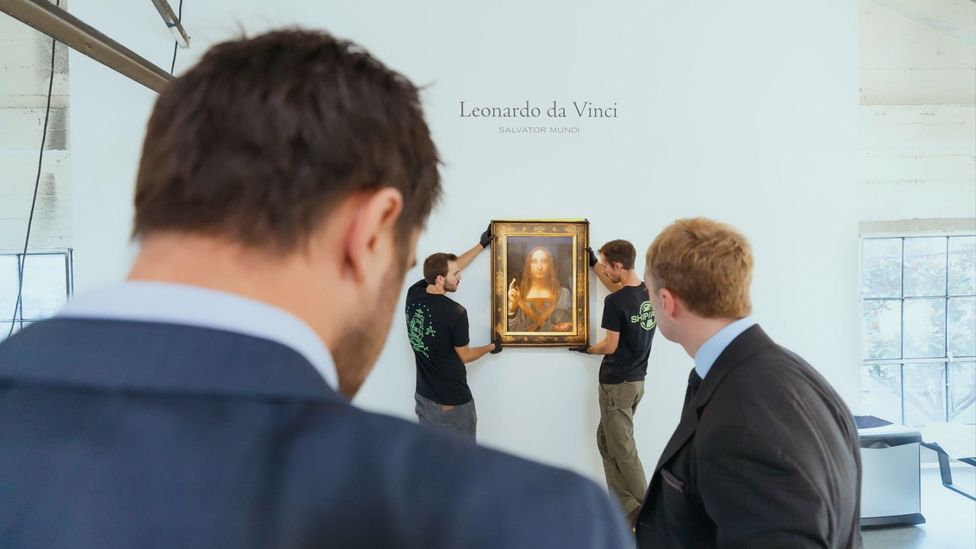

Leonardo da Vinci'south Salvator Mundi was sold by Christie'south in 2017 for a tape-breaking $450 million (Credit: Photo by Ilya S Savenok/Getty Images for Christie'southward Auction Business firm)

The quality of the painting itself divides people. The Usa fine art critic Jerry Saltz rails in The Lost Leonardo that "information technology's non even a skillful painting", much less a bully Leonardo, while true believers gush that seeing it in person is a transcendent feel. (Perchance so, just in the films and other reproduced images it does accept a more cloying look).

Some of the most eye-opening commentary in both films isn't even about art. In The Lost Leonardo, Evan Beard, a Bank of America executive who deals with fine art as investment, talks most the common buyers' motive of using artworks as collateral for other financial manoeuvres. The picture show doesn't take a stand on the painting'south attribution, just makes it clear that museums, dealers and potential buyers had millions to gain – forth with incalculable prestige – by choosing to believe it is a true Leonardo.

'Colourful characters'

A major turning bespeak came when the painting was controversially displayed every bit an authentic Leonardo at a 2011 exhibition at the National Gallery in London. In both films, Luke Syson, the curator of the show, stands by his decision. Just many experts on camera and elsewhere in the press think he leapt to an early conclusion. Alison Cole, editor of The Fine art Paper, has written extensively nigh the painting and saw it at the National Gallery. She tells BBC Culture, "Since so, Dianne Modestini continued to work on information technology. But when I saw it, it didn't sit comfortably with me every bit an autograph Leonardo." Yet, the exhibition went a long fashion toward legitimising a shaky attribution.

2 years later, some colourful characters entered the game. Yves Bouvier, a Swiss art dealer, bought the painting from the New York dealers for $83 million, reportedly on behalf of his client, a Russian oligarch named Dmitry Rybolovlev, though this is disputed by Mr Bouvier. Inside 2 days he sold it to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million. In The Lost Leonardo, a smile Bouvier says his exploits are just business as usual: "you purchase low and you sell high." (Swiss government investigated him for defrauding Rybolovlev over several artworks, merely this year closed the example without charging him.) Shortly, the painting was on its fashion to Christie'due south.

The Christie's sale itself was a highly staged drama, outset with a marketing video that showed not the painting but the faces of observers – nigh are ordinary people merely one of them is Leonardo DiCaprio – looking reverently at the image as if they were seeing Christ himself. The buyer was bearding, but the New York Times soon revealed him to be acting for bin Salman, a discovery that catapulted the painting into the geopolitical realm. At the time bin Salman was trying to burnish Kingdom of saudi arabia's image by loosening a few restrictions. Most art world observers thought the Salvator Mundi would be the centrepiece of a new museum or fine art centre in the region, but the painting has not been glimpsed in public since.

Information technology came close. The Louvre very much wanted to include it in its yard exhibition to celebrate Leonardo'southward 500th anniversary in 2019. Bin Salman himself visited President Emmanuel Macron in Paris while the loan was dangling in the balance. As late as the printing preview of the show, in that location was an empty space on the wall waiting for the Salvator Mundi, only it never arrived. The New York Times confirmed rumours that the Louvre wouldn't acquiesce to bin Salman's demand that his painting exist displayed in the aforementioned room as the Mona Lisa, giving it nigh-equal condition.

French President Emmanuel Macron pictured in 2018 with the owner of the Leonardo, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (Credit: Photo past Bandar Algaloud/Getty Images)

"The Louvre is supported past the regime, the ministry of civilization and ultimately Macron," Cole tells BBC Culture. "And it is involved therefore in the politics around culture. Then if Saudi Arabia decides that culture is going to exist the way it opens up and the Salvator Mundi is going to exist a fundamental thespian in that strategy and the Louvre is offering to exhibit information technology, then all those things are tied up together."

Cole was the kickoff to study, in March 2020, the existence of a 46-folio booklet the Louvre prepared for publication only never released, which asserts that the piece is an authentic Leonardo. Because the Louvre cannot annotate on privately-endemic works information technology has non displayed, the book can't be published, and at first, Cole says, the museum denied its existence.

Scandals and conspiracies

Antoine Vitkine'southward film Saviour for Auction is well-nigh notable for some explosive additions near what might have happened backside the scenes at the Louvre. The documentary covers much of the same footing as The Lost Leonardo, but less stylishly, with besides many stock establishing shots of cities. Information technology suffers from not having Modestini or another compelling central figure. Only it does take two anonymous sources, their faces hidden on camera, identified as high-ranking French government officials who had access to the Louvre's studies of the painting and to the French-Saudi negotiations. 1 of the sources says the Louvre concluded that Leonardo just "contributed to the painting," but that bin Salman would only corroborate the loan if the Salvator Mundi were labelled an authentic Leonardo. The source says he advised the government that "exhibiting under the Saudi conditions would be similar laundering a piece that price $450 1000000". The Louvre and the National Gallery refused to comment for either film.

The two documentaries arrive at a fourth dimension when films, podcasts and pop culture itself seem fascinated by art crimes, mysteries and forgeries. In the past yr two documentaries, the engaging Made Y'all Wait and the pedestrian Driven to Brainchild, tackled the case of the Knoedler Gallery in New York, which for nearly two decades sold forgeries supposedly past 20th-Century masters including Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. Knowingly or non? That is still a question. The Netflix serial This Is a Robbery delves into the 1990 theft of masterworks including a Rembrandt from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The series is full of conspiracy theories about the never-solved robbery.

And Lewis has a new viii-episode podcast, Fine art Bust: Scandalous Stories of the Art World, which promises stories of "the ugliest crimes, the biggest scandals and the murky in-between." The subjects range from Inigo Philbrick, criminally charged with defrauding clients by selling more than 100% of shares in artworks, to a gilded Egyptian coffin whose smuggled by came to light afterwards Kim Kardashian was photographed next to it at the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Constitute gala. The Met has since returned the coffin to Egypt. That these tales can work in a podcast, where no one can fifty-fifty run across the work being described, suggests how much the allure of today's art-criminal offence stories is in the skulduggery and mystery, not aesthetics.

A scene from Saviour for Sale, a second documentary well-nigh the Salvator Mundi, past French journalist Antoine Vitkine (Credit: Zadig Productions)

Many factors seem to take converged to create this flourishing moment for true fine art crime. There is so much information in the public sphere that everyone can take the illusion of being an insider. There are more and more platforms for telling stories. And Lewis points out that as the art marketplace has enlarged, our globe view itself has changed. The general mental attitude toward fine art criminal offence, he says, used to be shrugged off every bit "information technology's billionaires spending money, crooking each other", but today there is a realisation that "no, you can't loot that country's entire cultural heritage".

Among all these delightfully tangled histories, goose egg rivals the Salvator Mundi. Unless new documentation surfaces (unlikely after all these centuries), or a new scientific method of authentication arrives (also catchy because the piece of work has been and so damaged), the mystery may evidence eternal. "I'm admittedly sure that six months down the road or a year, there'south going to be some kind of new data, whether truthful or not, that's going to blow up everywhere in the news media," Dalsgaard says. "As long as this painting is hidden from the world and the time to come and fate of this painting is unknown, it'southward going to be clouded in a realm of mystery and the world will exist set to read anything new. Considering at the cease of the day, information technology'due south an entertaining story."

The Lost Leonardo is at present playing in the US and opens in the UK on 10 September.

Saviour for Sale opens in the U.s.a. on 17 September.

All episodes of the Fine art Bust podcast are bachelor now.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Civilization Motion-picture show and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to annotate on this story or anything else you take seen on BBC Civilisation, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if y'all liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Hereafter, Civilisation, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210819-where-is-the-worlds-most-expensive-painting

Posted by: schwartzhopoorand.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Can I Buy Sinclair Paint"

Post a Comment